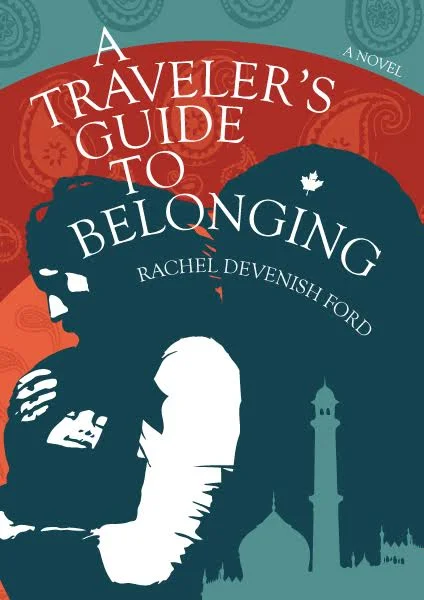

A Traveler’s Guide to belonging

:: A novel

"A beautiful, beautiful book." ~ Sara J. Henry, award-winning author of Learning to Swim.

From the author of The Eve Tree comes a travel story unlike any other, a tale of fathers and sons, love, longing and the search for home.

Timothy keeps getting rice in his baby's hair.

India is overwhelming even if you aren't 24 years old and a recently widowed new father, and Timothy isn't sure that he and his infant son will survive without a mother in the picture. he begins a journey through India with his baby, searching for a home in the new landscape of fatherhood, understanding of what this parenting thing is supposed to be, and a way back into life.

A Traveler's Guide to Belonging is a literary novel rich with emotion and description. If you like Anne Lamott, Barbara Kingsolver, or Ann Patchett, you'll love the book that one reader called, "Part travelogue, part spiritual journey, and part gentle romance."

Read it now to be transported to the stunning vistas and winding train tracks of India today.

Read on for excerpt.

a Traveler's guide to Belonging

Part 1

Chapter 1

Later, Isabel’s mother would say that her daughter died like a pig on the floor, but Timothy had been there, and he knew that Isabel’s death was nothing like the noisy, terrible death of a pig. It happened like this: Isabel was there and then she was gone, gone into the deep black Indian night, gone away from him and her newborn son, gone forever.

The day had started like all of their days since they had moved to the foothills of the Himalaya mountains in the far north of India four months before. Timothy and Isabel lived in a tiny, sun-soaked house surrounded by corn fields. When they had first seen the house, there had been wheat rather than corn, the tall stalks rippling gently as they walked up the curving paths from house to house, climbing stairs on the hillside where there were no roads, until Isabel put one hand on her belly, round with their baby, and declared she had to sit down or she would fall down. Timothy found a chair for her at a small café, then, at her bidding, had walked across the path to check out the little white house. The house turned out to be perfect, the very house where they would live and wait for their baby. They moved in and the wheat grew tall, then was harvested by women wearing punjabi suits with sweater vests, shawls wrapped around their heads. Corn was planted, and it grew, until that day when Timothy and Isabel woke up, not knowing they would be saying goodbye to each other forever.

The morning was so normal. They cuddled in their blankets until finally Timothy got out of bed to make the coffee on the burner in the corner of the room, wincing as his feet hit the cold concrete floor. From the pile of blankets, Isabel laughed at him.

“I was thinking Canadians were stronger than this,” she said.

“It doesn’t take long to forget the cold,” he said, rubbing his arms.

Isabel winced and rubbed her belly. “Ouch!” she said.

“Is he kicking you again?”

“Yes, and it hurts more today.”

“Maybe he’s wearing boots.”

They were used to calling the baby “him,” though Isabel hadn’t had an ultrasound and finding out the sex of the baby was illegal in India anyway, so really, they had no idea. Still, many women had approached Isabel and told her, “boy,” because they said they could tell by the shape of her belly or how she walked, or even what her face looked like. Timothy was hoping for a girl, actually, a girl exactly like Isabel, but he’d take a boy. Getting pregnant had been her idea, just a few months after their wedding, which was heartfelt but wouldn’t be recognized by any court at home. They had married in the desert in Rajasthan, where they tied their clothes together in the presence of a hunched, toothless old man with giant glasses, and his wife, even more bent, both of them clapping wildly at the happy marriage, the old man breaking into rusty song while his wife said, “Baba is a good singer, Baba is the best singer, you are very lucky to have Baba here today.”

“I need to have a baby soon,” Isabel had whispered to him, a few weeks later, in the darkness of their bed. Through the window Timothy could see endless stars; the lights were out for the night, there on the outskirts of the little town where they lived. He traced patterns in the stars with his eyes, unable to stop. He did the same with stones, or patterns in the marble, or the strangely psychedelic tiles in their tiny bathroom.

“Why soon?” he said. He was twenty-three, he’d just left his little brothers behind in Canada, an eight-year-old and ten-year-old who never could learn to knock before barreling into his bedroom. He came to India to experience something of the world, to learn about Indian music, to be the explorer he’d dreamed he was when he was a child. He was in no hurry to have kids.

“Because I just turned thirty-five, Timothy. I wouldn’t like to be one hundred years old when my children are twenty.”

He slowly turned to look at her. Her face looked like an angel’s face, the slight shadows under her eyes and the faint crow’s feet scattered in the corners the only indication that she was even a day older than him. Her brown eyes caught at him, and he leaned forward and kissed her.

“Only if I don’t have to change any diapers,” he said.

She smacked his arm. “You will not be that type of father!”

He laughed. “Ow! If you say so,” he said.

She reached up and stroked the side of his face. “Really, though, what do you think?”

“What about right now?” he whispered, and leaned in for another kiss.

“Really?” She sat up and jumped up and down on the bed, and he grabbed her around her rib cage and pulled her back to him.

“Really.”

As he straightened with two cups of coffee in his hands, she moaned a little again, and said, “I don’t know if that’s a kick, Timothy. It’s low in my back.”

He felt the blood quickly leave his face and then return.

“What do you mean? Should I get the midwife?”

She laughed. “First you must bring me my coffee. And then, yes, let’s call Liz.”

Liz told them to wait until the contractions were five minutes apart. And so they spent the day together, walking down the paths between stalks of corn, drinking mango lassis, the yogurt drink they both loved and gorged themselves on. Timothy gave Isabel back rubs when she wanted them, gave her distance when she wanted that. Liz came over in the evening and it all blurred together then, the panting and moaning, the pain Isabel was in, darkness falling outside. The few minutes of holding their boy. And then the worry turning to panic as the bleeding continued and there was so much of it and there was nowhere to go, no doctor to reach for, no ambulance to call. Their house so remote, a thirty-minute climb from any drivable road.

She was there and then she was gone. In the sudden stillness Timothy realized that he didn’t even know the precise moment that she left, that’s how quietly she slid away from them. All he could hear was the frantic pumping of his own heart, and there was nothing from hers; the quiet thud was gone. His face was still pressed to hers where he was kissing her, whispering that she was going to be okay, until he found that he was alone, talking to someone who was no longer with him. Time seemed to halt.

He blinked and saw stars. He heard the wails of their newborn son, swaddled and in the arms of the landlady, Sunita, who watched Timothy, her eyes filled with fear. The baby screamed because of the shock of cold on the chilly day, the brightness of the one bare lightbulb on the wall after the warm dark of the womb, and the fact that he was now thrust outside when he was accustomed to being inside. He could be comforted by a mother, but the baby’s mother was gone. Timothy sat back on his heels in panic. Did he shout? He didn’t know. The midwife was still massaging Isabel’s abdomen to try to get her uterus to contract and stop bleeding out. Tears were streaming down the midwife’s face and Timothy couldn’t get any sound out of his throat, tight as it was, to tell her that she could stop working; it was too late.

He looked at his wife’s pale face again, the eyes with their translucent lids that had fluttered closed moments ago. Nothing seemed real; just hours before she’d said “I think this is really it,” and they had been so excited, like children. They hadn’t known they were boarding a train they couldn’t escape. He was going to vomit. Isabel, gone. No.

He stood. Black and red specks danced in front of his eyes. He walked to the door of the small room with the peeling paint on the walls and looked out at the night. The baby cried harder and Sunita approached him on soft feet. He didn’t want to see the baby, he didn’t want to talk to anyone; he didn’t remember deciding to run but minutes later he found himself out in the night, pushing through wet cornfields. The stalks slapped him on the face, clinging to his wrists as he fought his way through; he didn’t plan a direction, he just ran. If he ran, his twisting gut seemed to tell him, it might all be different when he got back. Maybe nothing would have happened yet, maybe there would be a chance to make it turn out differently. As he ran, darkness clouded his mind and his thoughts slowed and became muddy.

He was soaking wet. He didn’t know how long he’d been running and walking and lurching. It wasn’t raining anymore, but the cornstalks were covered in water from the storm that had swept through a few hours before, so his pants clung to him and he put his palms to his eyes to wipe away water. Stopping wasn’t a good idea, though; he panicked again, looking around wildly for something, anything. Erase, he thought, sobbing now. Delete. Rewind. He would run away, never go back. He would leave this place now that Isabel was gone, he would climb into the mountains. He put out his hands and pushed through the plants again, nearly running smack into the bear that stood only ten feet away. Timothy stopped short and stood very still, holding onto a cornstalk with white fingers.

They’d been told, the last weeks, about bears in these Indian mountains.

“Don’t go too far in dark time,” Sunita had said with her rich Indian accent, standing at her doorstep with her baby, Beema, in her arms. “You are seeing these marks? The corn is break means bear is coming nightly.”

Isabel and Timothy tried to be careful, walking gingerly past the dark cornfields at night, coming home from dinner or late-night music with other travelers instead of by themselves, though they always loved walking alone in the darkness, stopping for kisses along the way.

Now Timothy was facing the bear and he was more alone than he had ever been in his life. So bring it, he thought. He hadn’t been careful; there wasn’t much use in being careful anymore. He had torn right into these fields as though he was looking for the bear.

It was an Asian black bear, and not so big, but standing on its hind legs, holding a stalk of corn in its front paws. The bear ate most of the cob of corn, husk and all, before dropping the stalk. The bear looked at Timothy. Timothy looked at the bear. Drops of cold water trickled down his forehead, into his stinging eyes, and he couldn’t raise his hand to wipe them. He couldn’t move at all. He stood and watched as the bear ripped another stalk out of the ground and ate the corn from it as well. Its claws left marks on the stalk when it dropped it, long scratches that turned Timothy’s stomach. He was going to be sick. Everything had changed the moment Isabel’s last breath left her. Now his world was dark, this hulk of bear revealing to him the danger and death under everything. Timothy whispered, “Please,” but there was no one to hear him. So he got louder. “Please!” he called, and then he shouted, “No! Get out of here! Just go!” The bear growled a low growl in its throat, dropped to all fours, and walked away from him, heading back toward the dark forest.

Timothy waited until he couldn’t see the cornstalks waving anymore, then turned, and there, under the himalayan stars and the bright moon, he vomited in the cornfield. He had been stopped short by the bear. He knew he couldn’t run away, he didn’t have whatever it took to run into the mountains, whatever it took to be a hermit, to leave his son and disappear. He squatted there for minutes or maybe hours, not even bothering to move away from the puddle of vomit, before he rose stiffly and walked back to the small house in the hills where a naked baby was screaming his hunger and cold in the injustice of a motherless world.